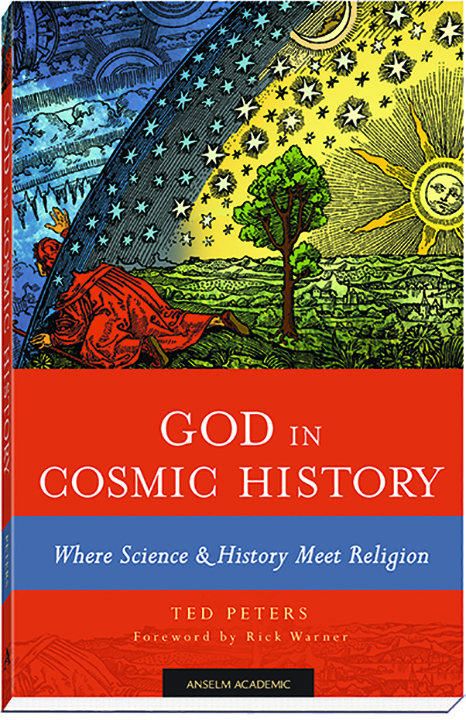

God in Cosmic History

Where Science and History Meet Religion

About This Book

Overview

Does a scientific account of human and natural history have room for the question of God?

Perhaps inadvertently, historians have often eliminated the religious chapters—those episodes in history during which human insights into transcendence and divinity have shaped human consciousness—from our planet’s story.

Ted Peters’s God in Cosmic History: Where Science and History Meet Religion tells the story of cosmic history as big historians tell it, beginning with the big bang, and explores the question of God hidden beneath this story. This expanded history begins with the big bang, offering a readable account of nature’s history before our hominid ancestors. God in Cosmic History pauses on the Axial Age of human history: a moment during the first millennium BCE in which questions of transcendence first simultaneously arose in distinct locations around the world. By exploring this threshold in cosmic history, Peters demonstrates the way the arrival of the God question marked a radical new human consciousness, one that ultimately laid the groundwork for the modern age.

Details

| Weight | 1.2 lbs |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 6 × 1.5 × 9 in |

| Pages | 358 |

| Print ISBN | 978-1-59982-813-8 |

| Format | Softcover |

| Item # | 7077 |

|---|

Customer Reviews

“In Ted Peters’s God in Cosmic History: Where Science and History Meet Religion, one of America’s top contemporary theologians insightfully connects our new scientific story of the universe to the long human quest for God. Such a delicate task is one that few writers are qualified to carry out in a manner that is both fully respectful of the natural sciences and also deeply rooted in religious wisdom. Ted Peters is the embodiment of such skill. His book should have wide appeal to readers of many backgrounds. Strongly recommended.”

Table of Contents

PA R T O N E

Cosmic History and the Origin of All Things

- Why Is History Getting Bigger?

- Big Bang Cosmology

- Sun, Earth, and Moon

- The Evolution of Living Creatures

- Our Pre-Human and Human Ancestors

- Religious Symbols and Spiritual Sensibilities

- Mythical Stories of Origin

- The Origin Story in Genesis 1:1–2:4a

- The Origin Story in Genesis 2:4b–3:24

- Critical Thinking about Cosmic History

- Fine Tuning, the Anthropic Principle, and the Multiverse

PA R T T W O

The Axial Question of God and the Future of Life on Earth

- War

- The Axial Breakthrough in China: Daoism and Confucianism

- The Axial Breakthrough in India: Hinduism and Buddhism

- The Axial Breakthrough in Greece: Philosophy

- The Axial Breakthrough in Israel: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

- Models of God

- Science and Scientism in Europe and China

- The Evolution Controversy

- Do We Share Our Galaxy with Extraterrestrial Neighbors?

- Toward a Just, Sustainable, Participatory, and Planetary Society

Afterword: Asking the Question of God

Index

Professional Reviews

Philosophy, Theology and the Sciences

Dr. Ted Peters has always liked to ask the God question Over his long and productive career, he has proposed this question in disciplines and topics as wide-ranging as cosmology, evolution, bioethics, exobiology, UFO’s, and even a spy novel This present, teacher-friendly book offers short chapters with both review and discussion questions as well as additional resources at the end of each chapter It is well suited and accessible for both college or seminary use Here Peters brings almost all of his wide range of interests together as he poses the God question to the emerging area of Big History According to Rick Warner, Big History describes the past in its largest spatial and temporal limits, from the big bang some 13 8 billion years ago to the future Human history is understood not only within a global context, as in World History, but within a galactic‑or cosmic context

Peters has no squabble with the scope of Big History, nor with its use of the natural sciences, but he does with what he perceives to be the intentional exclusion of religion from this historical narrative, including the question of ultimate meaning, the question of God The basic question is, “does a strictly scientific account of natural and human history require that we raise the question of God?” (11) Peters thinks that it does For Big History to ignore the question of God not only removes any discussion of ultimate meaning from the narrative, but also distorts the facts by leaving out of human history the significant role of religion Peters thinks that the omission of religion reveals a materialistic metaphysical bias in Big History He observes, When a theory preemptively excludes God from its description of reality, one may well ask, what presuppositions led to an answer that excludes appeal to God? They are not the presuppositions of solid science Rather, they are the presuppositions invoked by scientism Peters challenges this materialistic scientism bias and sets out to offer an alternative interpretation and critique of many of the topics covered within the realm of Big History He calls this alternative narrative Cosmic History and concludes, “Critical consciousness will permit the cosmic historian to find the question of God hidden beneath the story as the big historian tells it” To get a sense of how Peters challenges the scientistic presumption and what he offers as an alternative, this review will look briefly at a few select topics from each part of the volume After this, a few evaluative questions about the volume as a whole will be raised Authors e-offprint with publisher’s permission. Book Reviews Central to his argument is the understanding of the nature and meanings of history which he addresses in Part One: “Cosmic History and the Nature of All Things ” Peters begins by affirming that, “what makes history historical is contingency” and then offers four meanings for the term history He enumerates, First, history is what happened The term history refers to events that took place in the past … Second, history is an academic discipline which chronicles and interprets past contingent events … Third, to be historical is to be finite … sometimes called historicity. … To admit that one is a historical being is to say, in effect, that one expects to die … The fourth meaning of history – or, more specifically, effective history – refers to the influence of the past on one’s consciousness today (14–15; italics in original) It is really the third and fourth meanings of history that will open up the dimension of the ultimate He anticipates, There are, however, three items that this book’s version of Cosmic History adds that we don’t find in either World History or Big History: first, raising the question of human meaning through remembering the past and expecting the future; second, tracing the differentiation of human consciousness; and third, raising the question of God while analyzing how the historian tries to reconstruct the historical story … Here we will ask, might a theologian’s analysis of history illumine dimensions of reality missed byother historians? (18) Peters’ treatment of Big Bang cosmology is straightforward and as accurate to the scientific information as current observations permit Here we see that Peters’ squabble is not with science itself but with the framework (worldview) into which the scientific information is placed by Big History Peters notes, “Scientific stories are always meaningless, because the methods of science exclude meaningfulness at the outset” (34) But because science excludes questions of meaning in principle, it does not mean that the questions are illegitimate, but rather that they must be addressed by different disciplines such as philosophy and theology This is the core of Peters’ critique of Big History He concludes, “Because big historians have elected to swim only in the scientific ocean, we cannot expect them to provide meaning or ask the God question” (35) But the wonder and awe that scientific understanding opens up does demand questions of meaning and ultimacy Peters indicates that this quest for meaning has been present from the earliest pre‑historic expressions of homo sapiens and is later found in mythical stories of origin throughout human history (Chapters 6–7) Human contemplation of the sky leads to thinking about a ‘beyondness’ that can lead to a ‘beyond sensibility ’ He writes, “The beyond sensibility makes it possible for the human person to become aware of the possibility of a transcendent reality” (83) This transcendent awareness contributes to the formation of Authors e-offprint with publisher’s permission. Borrowing from Paul Tillich, Peters concludes that, “religion is the depth of culture and culture is the form of religion” (90) It is this element of transcendental awareness, according to Peters, that big historians avoid in their treatment of cultural formation and by doing so distort human history Peters critiques, “Big history does not teach about history Rather, it teaches history as a worldview, as the ground of life’s meaning, as the fundamental truth, as a substitute for traditional religion” (104; italics in original) By raising the question of origins, whether cosmological or anthropological, Big History is raising the questions of ultimacy whether it wants to admit it or not This part of the book then concludes by addressing the topics of “Fine Tuning, the Anthropic Principle, and the Multiverse ”

Most readers are familiar with the interesting information that cosmologists have raised about the ‘fine tuning’ of the universe This ‘fine tuning’ broaches the question of what has been called the Anthropic Principle which in its ‘weak’ form asks whether the universe simply allows for human emergence or in its ‘strong’ form intended for the emergence of intelligent beings such as humans The latter meaning pushes for some form of design or teleology which is strongly opposed by traditional scientific understanding While being developed to address cosmic inflation, the ‘multiverse’ is also one possible scientific solution to reducing this implication of purpose (148) By saying that anything that can possibly happen will happen, multiverse advocates propose an infinite number of universes in which one such as our own would occur Accordingly, fine tuning occurs by random chance in the vast panoply of possible universes, so intentional design is avoided There are a number of problems with this proposal, not the least of which is that such other universes cannot be scientifically detected Peters goes into some detail unpacking his arguments about this, distinguishing the ‘Principle of Plenitude’ (determinism) from the ‘Principle of Contingency’ (indeterminism. He then connects this to both positive and negative critiques of the existence of free will and finally to the cosmological argument Peters concludes, “The existence of a creator God is consonant with what we knowabout the big bang and its initial conditions A big bang cosmogony with God as the big banger would be coherent, given the data” (158) While the first part of the book is literally cosmic in scope, the second seeks to demonstrate the emergence of the question of ultimate meaning, the God question, in human cultural and religious history worldwide Here Peters draws heavily upon the theory of Karl Jaspers that an ‘Axial Age’ or an ‘Axial Breakthrough’ in consciousness occurred in many different cultures between 800 and 200 BCE, giving birth to the “higher religions” (184–86)

In separate chapters (13–16), Peters goes into some detail unpacking this breakthrough in cultures ranging from China and India to Greece and Israel He indicates that while differently expressed from culture to culture, the ‘Axial Breakthrough’ carries with it the opening to transcendence which creates a “deep cut dividing line” from homo sapiens to homo sapiens axialis He reports, “This axis does double duty: it is both the turning point of history as well as the connecting link between all cultures” (185–86)

Peters indicates that he intends to treat this theory as a ‘hypothesis’ observing, “Whether Jaspers is correct or not regarding the breakthrough of the Axial Period, an examination of his hypothesis will shed light on the effective history that structures our consciousness today” (187) This hypothesis does function, however, as the organizing principle in his treatment of this rich and diverse material Space does not permit summaries here, but suffice to say that they are engaging and for those not familiar with these religious and philosophical traditions these chapters would be good, if brief, introductions Addressing everything from ‘Young Earth Creationism,’ to ‘Intelligent Design,’ Theistic Evolution,’ and ‘Transhumanism,’ in the chapter “The Evolution Controversy” Peters offers a nice, concise summary of his critiques of the dimensions of this controversy to be found in many of his earlier works, concluding that creation and evolution can be compatible The chapter “Do We Share Our Galaxy with Extraterrestrial Neighbors?” gets into a topic that Peters has been interested in for a very long time Here, he nicely summarizes the scientific discoveries of exoplanets, the SETI Project and what the potential discovery of intelligent life might mean for human self‑understanding, including the development of ‘astrotheology’ (307) For purposes of this book, he also points out that the “ancient astronaut theorists” claimto be doing science If they can explain Biblical occurrences this way, “they can reduce any ancient insights into transcendent reality to strictly physical causes” (309) These arguments can be critiqued on scientific grounds and are seen as speculation based upon scientism, but also show why they too would work against serious consideration of religion.

Peters brings the summative chapters of the book to a close with the chapter, “Toward a Just, Sustainable, Participatory, and Planetary Society ” Here, he addresses the Anthropocene Epoch and the challenges of environmental degradation He moves to propose a “proleptic ethics” to provide a viable positive vision for the future including seven “middle axioms” that would build a bridge between a comprehensive ethical vision and practical moral action (320–27) This is where the discussion of a transcendent ultimate, of God, comes to ground hope and meaning to work for a viable future for the planet He concludes, if in fact Cosmic History is meaningless and directionless, then what happens on Earth will contribute nothing to the larger cosmic picture From whence, then, comes the grounding for an eco‑ethic? … Why bother? To ask about the warrant for caring for the earth raises the question of God (324) The absence of such a ground in the narrative of Big History is its most serious shortcoming Scientism can only ground a historical fatalism devoid of vision for change The main purpose of this part of the book is to demonstrate that the emergence of the question of ultimate meaning is a significant part of human cultural and religious history worldwide and should not be overlooked by Big Historians If we are to address the profound challenges that lie ahead, humanity needs more than this turning to some brief evaluation, one must ask whether Peters needs to buy into the Axial hypothesis as fully as he does in order to demonstrate the emergence of ‘higher religions’? This theory has been critiqued by a number of thinkers over the years and while not definitively disproven does add some unnecessary uncertainty to Peters’ argument because his argument demands the emergence of the awareness of transcendence and ultimacy, the ‘Axial Breakthrough’ is a convenient way to make this point It could, however, be done without getting into the question of the simultaneity or connectivity of these breakthroughs Peters is aware of this issue and brings it up in the afterword He indicates that, “This book has relied in large part on axial theory to help chronicle the course of differentiating human consciousness However, some problems with this approach must be confessed and addressed” (332) Here, he addresses two.

The first is the critique of the historical relativist that axial insight ‘privileges’ the higher religions at the expense of indigenous religions Peters observes, however, that there is an inconsistency in this critique for the veryappeal to justice and to equalize the treatment of religions itself comes from the axial insight The second critique is that this axial breakthrough really represents nothing but “Christianity without Christ” and overstates connectivity (333) Pannenberg, for example, thinks that Jaspers overemphasizes the role of the transcendental insight in forming human subjectivity and does not see this as justifying this epoch as an axis of world history (333) The great historian Eric Voegelin states, “I conclude that the concept of an epoch or axis‑time marked by the great spiritual outbursts alone is no longer tenable” (333) Peters brings these critiques up, but does not mount any significant defense against them, rather, he simply concludes that, “this hypothesis has been illuminating” (333) Even though he devotes nearly a third of the book to developing this hypothesis, he says he only wants to useit as an illustrative or ‘illuminating’ possibility He need not have spent so much time developing it if it was only for this purpose Summarizing the emergence of this insight in different cultures in slightly different ways can still stand without putting it together in an axial theory Peters’ point of the Big History oversight could still be made without resorting to Jaspers Critique of axial theory lays him open to the application of this critique to his own argument and unnecessarily weakens it.

Finally, Peters has written extensively about the relationship of religion and science over the years and has worked to develop different methodologies for approaching this relationship Yet, there is no serious direct treatment of this relationship in the book I think that unpacking that carefully would also have helped reveal the Big History metaphysical assumption of scientism Approaching it at the hermeneutical level and demonstrating that Big History at least tacitly assumes a ‘conflict’ model for the relationship would have given an additional critique beyond the straight historical narrative that he undertakes.

Granted, he perhaps sought to fight history with history here, but, as he clearly illustrates, the interpretation of history is rife with presuppositions that need to be exposed Is this book Peters’ Summa? I think not, but it is certainly a compendium of Peters’ thoughts and critiques on many of the various disciplines and topics that he has written about over the years He raises many important and intriguing points which stimulate one to pause and think If the reader would like to see how the question of ultimate meaning, the God question, can be cogently raised across many fields of scientific and historical inquiry, then this is the book for you.

God in Cosmic History

Where Science & History Meet Religion

Ted Peters

Winona, MN: Anselm Academic, February 2017. 358 pages.

$39.95. Paperback. ISBN 9781599828138. For other formats: Link to Publisher’s Website.

Review

God in Cosmic History describes the cosmos’ beginning with an exploding cosmic singularity. Ted Peters extends the interdisciplinary study of big history with theology. The questions are: Whether the universes originated from natural processes? Was God the author of the cosmos? or Might there be an argument for co-authorship?

Discussion of cosmic origins proceeds from “why there is something rather than nothing?” The prevailing responses include: 1) God created this unique universe from nothing ex nihilo as described in the Bible; 2) God created the universe and its natural laws and process which He conserves and continues to be active with; 3) God designed and created the cosmos as a mechanism which does not require His ongoing interaction; or 4) ours is a daughter universe destined by the laws of thermodynamics to fail and to spawn offspring. Having described the complexity of cosmic formation—including stars, earth, and moons—Peters next attends to the origins of life.

Peters frames development of life questioning, “How did the inorganic become organic?” (48). The two leading scientific theories are: 1) that material developed in a primordial soup on land; and 2) that life arose from compounds suspended in the ocean. Theory one states that an electric charge from lightning animated material containing chemicals—carbon, iron, hydrogen, etc. The second theory claims that chemicals and non-living material existed in the ocean. These material compounds were adrift on the currents and met volcanic energy. The inorganic material became living by heat energy, organisms crawled out of the pond or sea and then evolved.

A counter theory is that the bible is literal fact. God created life by the work of His hands. There is evolutionary doubt in the neo-creationist view. God instantaneously created the universe and life. He molded Adam from the earth then drew Eve from Adam’s side. The distance between then and now has been short, raising criticism that the fossil record or current scientific research does not correspond well with this view. There is another theistic evolutionary hypothesis.

Theistic evolution presents God creating the material essence, physical laws, and means for life to evolve. God is active in conserving life. Human people evolved to what they are today over a long natural process. Kenneth Miller, in Finding Darwin’s God: A scientist search for common ground between God and evolution (Harper Perennial, 2000) shows it is through the evolutionary process that the human brain and intellect developed the ability to receive the true revelation of God’s existence. Peters provides a dynamic analysis of Genesis as a faith and historical document that addresses the biblical creation story in contrast with Babylonian culture and science. Peters shows that Genesis is an account of natural cosmic and human development. The biblical account may reconcile with the Big Bang. God spoke the cosmos into existence out of nothing and breathed life into the instantaneous creation. Further, that any interpretation of Genesis and creation must address of a teleological future.

The biblical text presents God commanding that the primal duo of Adam and Eve abstain from the fruit of the Tree of Life. Eve, tempted by a spirit appearing as a serpent, eats the restricted fruit. In expression of free will, she succumbs to temptation. She shares the fruit with her mate and, exercising his free human will, he also partakes. The action breaks communion with the divine—visiting death upon creation. Peters states, “To replace God with oneself as ultimate is what the Greek myths called hubris and what the Latin Christians called pride” (119).

A break with God was initiated by the first humans, and communion with God is interrupted. That distance from God would forever place all human beings in a natural state of sin (original sin). The initially created environment described in Genesis was perfect and imbued with good. Peters reminds us that, “There is no abject evil in this story, only competition between a variety of good things” (120). Original sin is one of transmission rather than commission. Regardless, the story of Genesis prompts a reflection on an essentialness of human beings and points to universal violence and death.

At first, the way Peters locates the question of war and human violence appears strange. However, human beings seem to display the need for hope and reconciliation within themselves and with each other. Human beings are oriented toward goodness, but cannot fulfil or sustain that orientation in word, thought, or deed. Out of this tension, transformative critique and thought emerged that gave rise to new schools of thought, of science, and belief.

The axial advance was a dramatic progression of human understanding. In the ensuing historical period, we find breakthroughs in thinking in the Chinese, Indian, Greek, and Mesopotamian regions. Axial philosophers, seers, and thinkers developed a transformative means to conceive and critique ultimate reality, models for God were advanced, means for just and peaceful social order created, and the nature of what it means to be human is addressed. Peters’s exposure of the axial philosophical inquiry is broad. We are next led to consider the possible links with the future.

Gaudium et spes (The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, 1965) states we, “sincerely professes that all men, believers and unbelievers alike, ought to work for the rightful betterment of this world in which alike live; such an ideal cannot be realized, however, apart from sincere and prudent dialogue.” Peters’s work presents the questions of God in the context of being called out from cosmic and world history. The critical questions called forth are: does the personal good that human beings seek end with the grave, or is there a possibility of eternal existence in which we find ourselves reconciled and in full communion with a loving, almighty, and sovereign God? God in Cosmic History is commended for evoking a sincere and prudent dialog.

About the Reviewer(s):

David C. Martin is an independent Roman Catholic academic with foci in worldviews, religion, spirituality, social contructionism, and higher education.

About the Author(s)/Editor(s)/Translator(s):

Ted Peters is coeditor of the journal Theology and Science, published by the Francisco J. Ayala Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences at the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California. He is Research Professor Emeritus in Systematic Theology and Ethics at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary in Berkeley